The Schoolmaster Printer –

the Medieval Printing Press in St Albans

Here endyth this present cronycle of Englonde wyth the frute of tymes, compiled in a booke and also empryted by one somtyme scole mayster of saynt Albons, on whoos soule God have mercy (Wynkin de Worde, 1497)

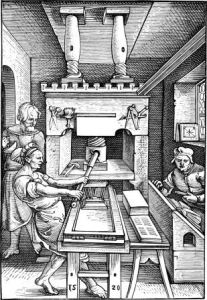

After the first book printed with movable type had had its debut at the Frankfurt Fair in 1454, Johannes Gutenberg’s invention quickly spread all over Europe.

William Caxton was the first to bring printing to England, when he set up his workshop in Westminster in the mid-1470s (either 1475 or – more probably – 1476). Two years after Caxton opened his shop in Westminster, another printing press, in Oxford, published its first book (in 1478). However, given my personal interest, I would like to find out more about the third English printing press – in St Albans.

This printer is referred to as the “Schoolmaster Printer”, because Wynkin de Worde, who had taken over his master’s business after Caxton’s death in 1492, said in 1497, when reprinting the Chronicles of England, that these had previously been printed by “one somtyme scole mayster of saynt Albons, on whoos soule God have mercy”.[i]

Eight books survive from the early St Albans printing press. Unfortunately, nothing is known about the identity of the Schoolmaster Printer, nor is it certain whether he was indeed a schoolmaster and whether there was just one printer or two.

Sir Henry Chauncy, who speculated about him in 1700, tells us that he was “John Insomuch, a Monk and Schoolmaster in this Town, [who] erected a Printing Press in this Monastery” and said that he was the next after Caxton in London.[ii] Unfortunately, he was wrong on almost all counts.

As already explained above, we now know that the St Albans press was the third in England, after London and Oxford, not the second.

The name “John Insomuch” is a misunderstanding from the opening words of his two books in English: “Inso myche that it is necessari” in the prologue to the St. Albans Chronicle, and “In so moche that gentill men and honest persones” from the Boke of St. Albans. [iii] We don’t know how Chauncy came up with the first name John. However, St Albans School still owns a company, incorporated in 1996, with the name ‘John Insomuch Schoolmaster Printer (1479) Limited’.[iv] (The first book printed by the Schoolmaster Printer has been dated to 1479.)

If this printer was indeed a schoolmaster, he would have taught at the grammar school in St Albans. This school had been a secular school right from the start, therefore the Schoolmaster Printer would not have been a monk.[v]

We do not know either where the printing press was located. Although Chauncy said that it was at the abbey, this is probably also not true. The school was not inside the abbey and the colophons of some of the books printed by the Schoolmaster Printer state that they were printed in the town of St Albans, not the abbey. In his device, the printer used the saltire on a shield, but this was both the arms of the abbey and the town.

The Victoria History of the County of Hertfordshire is somewhat confused on this point. In the part covering St Albans Abbey, it states that the printing press was “supposed to be” in a first floor room of the Abbey Gatehouse (except for the church this is the only building of the abbey to have survived to today). On the other hand, the chapter covering St Albans School, which also deals with the Schoolmaster Printer, points out that the colophon of the Rhetorica nova explicitly reads “in the town”.[vi] While the Gatehouse would have provided the security such an enterprise would need, it was part of the abbey, so why should the printer have said the books were printed “in the town”? In addition, looking at the building makes me wonder, whether the space would have been sufficient. And why move all the heavy equipment up to the first floor, when it would have been much easier to use a suitable room at ground level?

Early in the 20th century, William Page (who also edited The Victoria History of the County of Hertfordshire) discovered the will of “John Marchall, schoolmaster of St. Albans” and in his first excitement jumped to the conclusion that this could be the elusive Schoolmaster Printer. However, it seems unlikely that this is our printer either. Wynkin’s words “on whose soul God have mercy” indicate that the printer was dead by the time Wynkin wrote this in 1497, but John Marchall only died in 1501 (his will is dated 21 January 1501 and was proved on 8 March of that year). Page’s mistake is corrected in the VCH, published 7 years later.[vii]

However, even though John Marchall is not the Schoolmaster Printer, his will tells us something about the kind of man his predecessor might have been. Marchall was a layman and married, as he left his property to “Joan his wife”. He seems to have been on good terms with the abbot, as his executor was “John Killingworth, cellarer of the monastery, by licence of the abbot”. The school must have been of a reasonable size, as there was not just the schoolmaster but also an usher – his witnesses were “William Stepneth, mercer, and William Smyth, usher of the school aforesaid”. Marchall wished to be buried in the chancel of the Church of St Andrew, “next the place where he was accustomed to sit”. This parochial church, dedicated between 1094 and 1119, was at the north-west corner of the abbey church. The schoolmaster must have had a high standing in the community, if his usual seat was next to the chancel and he could request to be buried in the chancel.

It seems that unlike the (second) printer in Oxford, Theoderic Root, who came from Cologne, the St Albans printer was English. To judge by the phrases he used, he probably came from the north. His spelling is phonetic.[viii]

Some experts suggest that he worked closely with Caxton in London, going as far as to suggest that “the St Albans press was a provincial branch, so to speak, of Caxton’s”. Others, however, emphatically deny any connection. William Blades in his introduction to a facsimile edition of The Boke of St Albans answers his own question “Was he connected with Caxton and the Westminster press?” – “Without a shadow of doubt I say, No!”.[ix]

Though St Albans School was not part of the monastic community, the Schoolmaster Printer would not have been able to carry out his work without the approval and possibly even the financial backing of the Abbey of St Albans. St Albans was a Benedictine abbey, an order which placed a strong emphasis on learning. They were proponents of the intellectual revival of the Italian humanists in the 15th century. St Albans looked back on a long tradition, going back to at least the first Norman abbot Paul de Caen (1077-1093), in “library-building, book-making [manuscripts], … the skilled writing and lavish decoration of books”. Abbot Paul had founded the scriptorium and endowed three writers to copy books. By the time of the Schoolmaster Printer, books had been copied in St Albans for 400 years, indeed it was one of the most productive Benedictine abbeys in England. Probably the best known is the St Albans Psalter.[x] The printer just continued this tradition by other means.

The printing press was operating during the abbacy of William Wallingford (1476-1492). While William Wallingford’s reputation is somewhat mixed, there is no doubt that he supported education and scholarship and has been credited with encouraging the printer. However, already one of Wallingford’s predecessors (and his adversary), John of Whethamstede (1420-1440 & 1452-1465), had gone to great efforts to secure works of Italian humanists for the abbey’s library, which he himself described as ‘the best in the whole country’. St Albans School had its own famous library and though it no longer exists, it is known to have included a number of early printed books.[xi] The long and prestigious history of the scriptorium combined with this atmosphere of learning seems to have been just the right environment for a printing press in St Albans.

The following eight books are known to have been printed by the press in St Albans:

- 1479 – Elegantiolae by Augustinus Datus, a grammatical textbook (not dated)

- 1480 – Margarita eloquentiae, sive Rhetorica nova by Laurentius Gulielmus Traversanus de Saona (“Impressum fuit hoc presens opus rethorice facultatis apud vill[am] Sancti Albani Anno domini MCCCCLXXX”)

- 1480 – Liber modorum significandi by Eccardus Albertus (“Apud villam Sancti Albani”)

- 1481 – Quaestiones super Physica Aristotelis by Johannes Canonicus

- 1481 – Exempla Sacrae Scripturae ex utroque Testamento collecta by Nicolaus de Hanapis

- 1481-82 – Scriptum in logica sua by Antonius Andreae

- 1486 (? – see below) – Chronicles of England (“In the yeer of Our Lord MIIIICLXXXIII and in the XXIII yeer of Kyng Edward the fourth at Saynt Albons”)

- 1486 – The Boke of St Albans or Book of Hawking, Hunting, and Heraldry[xii]

His first book, the Elegantiolae, is a small textbook for teaching Latin, which could have been used in the grammar school. The type used in this book only appears in this book (except as page signatures in the next book).

The second book is a series of lectures on rhetoric given in Latin at Cambridge University by the Franciscan friar Laurentius Gulielmus Traversanus de Saona, which had first been printed by Caxton in 1478. If the number of surviving copies is anything to go by, the Schoolmaster’s edition seems to have been more popular than Caxton’s.[xiii] It would also have been suitable to be used at St Albans School. Though the type of this book shows some similarity to Caxton’s, it also has its own distinct features.

The following four Latin books are all of a more advanced level, more suited for use at a university. It has therefore been suggested that these were aimed at purchasers from Cambridge, where no press had yet been established. [xiv] All were printed in the same type, according to Duff “quite the ugliest and most confusing of English fifteenth-century types, and full of bewildering contradictions”.

The last two books are completely different from the first six. Not only are they in English instead of Latin, but they also have a different target market, laymen rather than students. Because of these differences, some authors have suggested that they were the work of a different printer.[xv] The Boke of St Albans states that it was compiled in 1486, so it cannot have been printed earlier. Though the Chronicles of England include at the end of the prologue the above quoted reference to 1483 and Edward IV, it has now been widely accepted that it was actually printed at around the same time as the Boke of St Albans, as their typography is closely connected.

The Chronicles of England are an extended version of the Chronicles first printed in 1480 by Caxton. Both contain a comprehensive history of England up until 1461. The St Albans printer added a history of the popes and ecclesiastical matters, as well as a prologue on the use of history. It is the first book printed in England to contain a printer’s device,[xvi] featuring a saltire cross on a shield, the arms of both the abbey and the town of St Albans. It includes some red printing used in initials and paragraph marks as well as a few diagrams and one illustration.

The Boke of St Albans is a “book of hawking and hunting and also of coat of arms”. It is the earliest known example of colour printing in England. At the end of the second part of the book, on hunting, we find “Explicit Dam Julyans Barnes in her book on hunting”. There are various theories who “Dam Julyans Barnes” was. The content is mostly derived from earlier treatises.

If all eight books were printed by the same man, rather than two, the gap between the first six and the last two is interesting. Is it a coincidence that the gap corresponds roughly with the reign of Richard III? As far as I can see, nobody has speculated on any connection of the printer to the political turmoil during this time. Maybe it is just the wishful thinking of someone interested in Richard III to see a possible connection? To find any possible connection, we have to look at one between Richard III and the people around him and St Albans.

In trying to score up Brownie points with the government of the day, abbot Wallingford appointed William lord Hastings seneschal or steward of the liberty of St. Albans in 1479, although a previous abbot had in 1471 granted the same office to John Forster for life.[xvii] He tried to rectify this by giving the office jointly to both of them in 1482.

John Forster was a local lawyer, who owned the manor of Mawedelyne near Berkhamsted and had acted on various commissions of the peace and as MP. In addition, he was the receiver general of Edward IV’s queen, Elizabeth Woodville. In 1482, to appoint Hastings and Forster jointly might have been a sensible solution. Hastings was no doubt a political move, but as he was very much involved in national affairs at court, the local lawyer would have been able to do the day-to-day administration, including serving as judge in the civil courts. Then came that fateful Friday, 13 June 1483, when Hastings was executed. Forster was arrested at his home in Hertfordshire (Mawedelyne?) and taken to the Tower. He was released later and tried to buy his way out of trouble by releasing certain manors as well as his office of steward. The office of steward was then granted to William Catesby, the man of choice during Richard III’s reign. Nothing else is known of John Forster until he got another commission of the peace one month after Bosworth, on 20 September 1485. He continued in this role until his death in 1488. A local man of influence, like the schoolmaster, might have had a connection with Forster (the local man seems more likely than Hastings) and this might account for the interval in his printing activities during Richard’s reign. Without having a name for the printer, it is difficult to find any information though.

The question remains why the St Albans press ceased work in 1486. The reason might simply be that the printer fell ill and died, as we know he was dead by 1497. However, the first press in Oxford also stopped in 1486. The demise of both has – indirectly – been blamed on Richard III.

Incidentally, Richard III’s chancellor, John Russell, was one of the first two Englishmen, who are known to have owned printed books. He bought, on 17 April 1467, an edition of Cicero, De officiis and Paradoxa, printed by Fust and Schoeffer (Gutenberg’s Apprentice) in 1466, during a trip to Bruges.[xviii] While souvenirs like his had not attracted any duties, as neither had manuscripts, the huge increase in imported books during the next decade made the desire for some standardized form of bill of custom understandable.[xix]

Probably to satisfy English merchants, Richard’s only Parliament of 1484 passed an act to limit the activities of foreign merchants in England. There is, however, an important proviso, exempting all merchants and craftsmen concerned with the book trade from the scope of the act. It said that it did not apply to “’any Artificer or merchaunt straungier of what Nacion or Contrey he be or shalbe of, for bryngyng into this Realme, or sellyng by retaill or otherwise, of any maner bokes, wrytten or imprynted, or for the inhabitynge within the said Realme for the same intent, or to any writer, lympner, bynder or imprynter of suche bokes as he hath or shall have to sell by way of merchaundise, or for their abode in the same Reaume for the excercisyng of the said occupacions”.[xx] This has been accepted as being on the personal intervention of Richard, who was known as a bibliophile. Clearly, Richard’s government and his chancellor John Russell were not against a supply of good books, but the international competition might have harmed the smaller English printing presses.

A later press was operating in St Albans from at least 1534 (possibly earlier) until the dissolution of the abbey in 1539. At the helm was a John Herford, who worked closely with abbot Robert Catton (1531-1538) and especially with the prior and last abbot Richard Boreman or Stevenage (1538-). Unlike the first printing press, this one made no secret out of its close involvement with the abbey. In the end, Herford seems to have printed something rather indiscreet and abbot Richard quickly sent a letter telling Thomas Cromwell that it had nothing to do with him. Nevertheless, two months later the abbey was handed over to Henry VIII’s commissioners. The workshop was dismantled and taken to London, where a Nicholas Bourman used the equipment for a short time. Given his last name, he might very well have been a relative of the last abbot. It seems Herford was imprisoned, but he was released in 1544 and the material returned to him. However, Herford did not return to St Albans and this was the end of book printing in the town.[xxi]

Notes:

[i] Blake, N.F., ‘Worde, Wynkyn de (d. 1534/5)’, Oxford DNB (Jan. 2008) [last accessed online 4 Feb. 2011]. Duff, E.G., The English Provincial Printers, Stationers and Bookbinders to 1557, Forgotten Book, 2015 (reproduction of the Cambridge University Press edition of 1912), p. 34

[ii] Chauncy, H., The Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire. B.J. Holdsworth, 1826 (original work published 1700), p. 284

[iii] Ashdown, C.H., ‘The Schoolmaster Printer of St Albans’, Trans. SAHAAS (1924), pp. 76-79. URL: http://www.stalbanshistory.org/documents/1924_07_.pdf [last accessed online 22 Feb. 2014]; Duff, p. 34

[iv] ‘John Insomuch Schoolmaster Printer (1479) Limited’, endole UK Company Insights. URL: http://www.endole.co.uk/company/03187456/john-insomuch-schoolmaster-printer-1479-limited [last accessed 14 Oct. 2015]

[v] Galbraith, V.H., The Abbey of St. Albans from 1300 to the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The Stanhope Essay, 1911. B. H. Blackwell, Broad Street, 1911, p .64. Online URL: http://lollardsociety.org/pdfs/Galbraith_StAlbans1300on.pdf)

[vi] Duff, E.G., p. 35; ‘St Albans abbey: The monastic buildings’, in A History of the County of Hertford: Volume 2, ed. W. Page. London, 1908, pp. 507-510. British History Online URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/herts/vol2/pp507-510 [last accessed online 26 June 2015]; VCH, pp. 55-56

[vii] Page, W., ‘St Albans School and its Schoolmaster Printer’, in: The Home Counties Magazine, 1901 (Vol. 3). Forgotten Books, 2013 (Original work published 1901), pp. 79, further references to John Marchall’s will are based on this; VCH, p. 56

[viii] Ashdown, C.H., p. 79

[ix] Barker, N., ‘The St Albans Press: The first punch-cutter in England and the first native typefounder?’, Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, vol. 7, no. 3 (1979), p. 258; but Blades, W., ‘Introduction’, The Boke of St Albans by Dame Juliana Berners Containing Treatises on Hawking, Hunting, Cote Armour: Printed in St Albans by the Schoolmaster-Printer in 1486, Facsimile Reproduction, London, 1901. Online URL: https://archive.org/stream/bokeofsaintalban00bernuoft#page/34/mode/2up [last accessed 25 Oct. 2015], p. 19

[x] Thomson, R.M., Manuscripts from St. Albans Abbey, 1066-1235: Plates. Boydell & Brewer, 1982, p.2; Roberts, W., Printers’ Marks. A Chapter in the History of Typography. George Bell & Sons, London, 1893, p. 35; Hourihane, C., The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture, vol. 2. OUP USA, 2012, p. 427

[xi] Clark, J.G., ‘Wallingford, William (d. 1492)’, Oxford DNB (online 23 Sept. 2004) [last accessed online 20 Jan. 2011]; Clark, J.G., ‘Whethamstede , John (c.1392–1465)’, Oxford DNB (online 23 Sept. 2004) [last accessed online 1 Jan. 2012]; Barker, N., p. 257

[xii]Unless otherwise stated, the following is based on: ‘Monastic Printing and the press at St Albans’, The John Rylands University Library, University of Manchster. URL: http://www.library.manchester.ac.uk/firstimpressions/assets/downloads/11-Monastic-Printing-and-the-press-at-St-Albans.pdf [last accessed 5 Nov. 2015]; Duff, E.G., pp. 34-41; Ashdown, C.H.

[xiii] Murphy, J.J., ‘Laurentius Guglielmus Traversagnus and the Genesis of Vaticana Codex Lat. 11441, with Remarks on Bodleian MS Laud Lat. 61’, in: Middle English Texts in Transition: A Festschrift Dedicated to Toshiyuki Takamiya on His 70th Birthday, ed. S. Horobin & L.R. Mooney. York Medieval Press, 2014, p. 242

[xiv] Orme, N., Medieval Schools from Roman Britain to Renaissance England. Yale University Press, 2006, p. 181; Ashdown, C.H., p. 78

[xv] For example Barker, N., p. 268

[xvi] Coleman, J., ‘The Chronicles of England’, University of Glasgow, Special Collections (Sept. 2001). URL: http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/exhibns/month/sep2001.html [last accessed 6 Nov. 2015]; the illustration is from Roberts, W., Printers’ Marks. A Chapter in the History of Typography. George Bell & Sons, London, 1893, p. 56. Online URL: https://archive.org/stream/printersmarkscha00robeuoft#page/56/mode/2up

[xvii] The following is based on: Rogers, I., ‘John Forster (d.1488)’, www.girders.net [last accessed 13 Nov. 2015], referencing J. C. Wedgewood, History of Parliament 1439-1509, vol. I: Biographies of Members of the Commons, pp. 345-346; Ford, D.N., ‘William of Wallingford (d. 1492)’, David Nash Ford’s Royal Berkshire History. URL: http://www.berkshirehistory.com/bios/wwallingford.html [last accessed 6 Nov. 2015]; Moorhen, W.E.A., ‘William, Lord Hastings, and the Crisis of 1483: An Assessment’, Richard III Society. URL: http://www.richardiii.net/2_5_0_riii_controversy.php [last accessed 6 Nov. 2015]; Newcome, P., The history of the ancient and royal foundation: called the Abbey of St. Alban, in the county of Hertford, from the founding thereof, in 793, to its dissolution, in 1539. J. Nichols, 1793

[xviii] Unless otherwise stated, the following is based on: Armstrong, E., ‘English Purchases of Printed Books from the Continent 1465-1526’, The English Historical Review, vol. 94, no. 371 (April 1979), pp. 268-290; Kleineke, H., ‘Richard III and the Parliament of 1484’, The History of Parliament Blog (26 March 2015). URL: https://thehistoryofparliament.wordpress.com/2015/03/26/richard-iii-and-the-parliament-of-1484/ [last accessed 8 Nov. 2015]

[xix] Armstrong, E., p. 273

[xx] Statutes of the Realm, quoted in Armstrong, E., p. 276

[xxi] Duff, E.G., pp. 101-104

The practice of using, as your surname, the locality in which you were born is noticeable in the names of the Abbots of St. Albans such as Wallingford, Alban and Wheathampsted. So it is possible that our so called authoress used a nom de plume. If you look on Charles Smiths 1808 map of Hertfordshire you will notice within sight of Sopwell Nunnery the hospital St. JULIANS and within sight of that is Sopwell BARNES. Now there is a thought. Also who was Elizabeth Catherine Holstead, gentlewoman and widow? She certainly was significant, and respected by the Abbot when he personally appointed her Anchorite.

LikeLike