The Eulenspiegel Fountain in Braunschweig

Braunschweig, in Lower Saxony, Germany, is a city rich in history. This became clear to me, when I recently had the opportunity to revisit the city where I was born. We moved away when I was seven, long before its history held much interest to me. Seeing it again, brought back to me the stories my grandfather used to tell me. He was a wonderful story-teller. His range covered stories by others (sometimes embellished to make them more attractive for his little granddaughter), and above all stories he made up on the spot, linking them to the buildings or monuments around us.

I would like to share with you a monument to one of the heroes of the stories he told me: Till Eulenspiegel. It’s not very often that you get a chance to touch one of the heroes of the stories of your childhood. However, this was what I able to do when I saw the Eulenspiegel for the first time, at the age of four or five. Needless to say, I went back to say “hello” to Till now.

A collection of stories featuring Till Eulenspiegel was first published anonymously in Strasburg in the early 16th century. Within 15 years, the book was translated into other languages and became an early bestseller among printed books. That is how far established facts go. There is debate about the author of the book. It has been suggested that it was written by Hermann Bote (c. 1467-1520), a customs scribe in Braunschweig, but others reject this theory. The same applies to theories whether the character Eulenspiegel is based on an actual person. The character is said to have lived approx. 1320 to 1350, but not all historical events mentioned in the stories fit into that time frame. He may – or may not – have been based on the real-life Thile von Kneitlingen. Kneitlingen is a small town near Braunschweig.

Three of the 95 stories take place in Braunschweig. One of these, where Eulenspiegel works in a bakery, is depicted in the fountain. According to the story, his master instructed him one evening to work overnight without supervision. Till asked what he was supposed to bake. The baker, irritated by this silly question, replied “owls and guenons” (a kind of monkey). And this is exactly what Till did. The next morning, his boss was not impressed and chucked Eulenspiegel and his bread animals out. Though he came to regret this, when Till sold the baked goods for a lot of money in town.

The fountain is the work of sculptor Arnold Kramer (1863-1918). He originally came from Wolfenbüttel, near Braunschweig, though by this time he lived and worked in Dresden. The first designs of the fountain were done in 1903 and during 1904 a model was completed. In January 1905, this was first shown in Dresden. When the model was exhibited in May in Braunschweig, it was an immediate success.

On 23 June 1905, a group of influential citizens met to discuss acquiring the fountain for the city. They expected the costs to amount to 15 000 Marks, a small fortune at the time. It was decided to finance it by asking for donations from citizens, rather than using public funds.

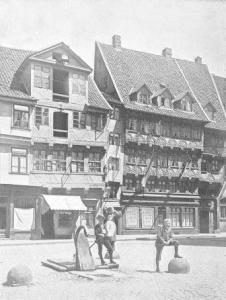

They also decided that the best place for the fountain would be the Bäckerklint, a square in Braunschweig, where a bakery claimed to be the one where Eulenspiegel had baked his owls and guenons. A bit of an optimistic claim, as the then-existing building only dated from the 1630s. Obviously not old enough for Eulenspiegel, who was said to have lived in the 14th century. Nevermind, perhaps the building had replaced an earlier bakery.

The term “Klint” has been in use for the square at least since the 12th century. “Klint” means a small elevation from the flood plains of a river. The first record of it as “Bäckerklint” dates from the 14th century. It has been suggested that in this area there may have been many bakeries, because the proximity to the river Oker provided sufficient water in case of fires. In the early 20th century, the square was an impressive setting, boasting a great number of half-timbered buildings. Braunschweig is said to have been the largest half-timbered city in Germany.

The problem of how to finance the project was quickly solved. The banker Bernhard Meyersfeld, one of the citizens attending the original meeting, came forward and donated the 15 000 Marks needed. Meyersfeld is remembered for his generous donations to various charities in the city.

Now the plans could progress very fast. Just two weeks after the original meeting, a provisional fountain was erected, which found general approval. The actual fountain took a bit longer and also involved additional costs, which were again largely met by Meyersfeld. The mayor promised that the city would pay for the necessary reorganisation of the square and the water supply.

The fountain was unveiled on 27 September 1906. In the inscription on the back, the city thanked Bernhard Meyersfeld for his donation. The fountain shows Eulenspiegel taking a break from his work at the bakery and sitting on the edge of a well. He is surrounded by the owls and guenons. The figure of Till himself was inspired by a statue from 1639.

In the 1930s, the National Socialists removed the part of the inscription mentioning the Jewish donor Bernhard Meyersfeld. Meyersfeld himself had died in 1920, but his family managed to emigrate to South Africa in time.

During a bomb raid and an ensuing fire storm in the night of 14 to 15 October 1944, the old half-timbered buildings on the Bäckerklint were destroyed, along with 90% of the old town of Braunschweig. Miraculously, the fountain survived virtually unscathed.

When Braunschweig was rebuilt after the war, a policy of “tradition islands” was followed, where buildings around historic sights, often churches, were reconstructed following plans and photographs of the old buildings. In other areas new buildings were erected. Unfortunately, the Bäckerklint was not one of the “tradition islands”. During the reconstruction the fountain was removed, but was unveiled again on 1 October 1950. It has a new inscription, thanking its generous donor Bernhard Meyersfeld again.

Even if the setting is not quite as picturesque as it must have been before the war, the fountain itself is well worth a visit. After all, it’s not very often that you get a chance to touch the heroes of the stories of your childhood.

Further Reading:

Blume, H., ‘Hermann Bote: Braunschweiger Stadtschreiber und Literat’, Braunschweiger Beiträge zur deutschen Sprache und Literatur, vol. 15 (2009)

Braumann, R., ‘Serie: Braunschweig, deine Straßen – Bäckerklint’, Regional Braunschweig (23 March 2015). URL: http://regionalbraunschweig.de/serie-braunschweig-deine-strassen-baeckerklint/ [last accessed 17 July 2016]

Hucker, B.U., ‘War Tile von Kneitlingen (1339-1351) der historische Till Eulenspiegel?‘, Braunschweigisches Jahrbuch, vol. 64 (1983), pp. 7-24

Meier, H., Die Straßennamen der Stadt Braunschweig. Quellen und Forschungen zur Braunsschweigischen Geschichte, vol. 1 (1901), pp. 14-15

Ostwald, T., ‘Narr oder Raubritter? ‘, Der Loewe (7 Sept. 2015). URL: http://www.der-loewe.info/narr-oder-raubritter/ [last accessed 9 July 2016]

Schwarz, H.J., ‘Der große Unbekannte’, Spiegel Geschichte, no. 4 (2013), pp. 72-3. Online URL: http://magazin.spiegel.de/EpubDelivery/spiegel/pdf/104108142 [last accessed online 11 July 2016]

Steinführer, H., Der Braunschweiger Eulenspiegelbrunnen. Richard Borek Stiftung, 2014

Wunderlich, W., ‘Till Eulenspiegel: Zur Karriere eines Schalksnarren in Geschichte und Gegenwart’, Monatshefte, vol. 78, no. 1 (1986), pp. 38-47

You can read the story of Till Eulenspiegel as a baker’s journeyman here (in German): http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/till-eulenspiegel-1936/62

Pingback: The Gewandhaus in Braunschweig | Dottie Tales